With his beard, unkempt hair and stern look, there is an aura of a revolutionary about Sócrates. In some ways he was the footballing equivalent of Che Guevara, with his political opinions backed by his activism.

To add weight to his mystique, Sócrates was one of the most elegant and gifted players to wear the yellow shirt of Brazil. He was also part of the 1982 and 1986 World Cup squads that played some of the most beautiful football ever seen at a major finals. With the likes of Falcão and Zico, it was a talented team that tore apart the opposition and scored spectacular goals like Sócrates’ equaliser against the Soviet Union. All that seemed to matter to that Brazil teams of 1982 and ‘86 was the joy that they brought to people. They were Garrincha, just a few years later.

Many Brazilians have fond memories of ‘The Doctor’, as he was nicknamed due to qualifying in medicine. Rumour had it that Socrates studied at University College Dublin but sadly was confirmed as an urban myth. He was seen as a leader of the people, who was kind and brought happiness with his football. Politics was also a passion of Sócrates, who had his eyes turned to the social injustices in his country.

Brazil during the 1960s and ’70s was a country ruled by a military junta following the 1964 Brazilian coup d’état, and culminated in the overthrow of the democratic João Goulart government. The previous regime was deemed to be a “socialist threat” by the military and the right-wing, who opposed policies such as the basic reform plan which was aimed at socialising the profits of large companies towards ensuring a better quality of life for Brazilians.

With the support of the US government, Goulart was usurped with Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco sworn in as the president. Initially the aim of the junta was to keep hold of power until 1967, when Goulart’s term would expire, but ultimately felt that they had to keep control to contain the “dissenters” within the country.

Protests against the junta were brutally put down with dissenters killed, tortured or having to flee the country. Repression and elimination of any political opposition of the state became the policy of the government. The current Brazil president Dilma Rousseff was one of those who was imprisoned and tortured on the instructions of this totalitarian regime.

The organisation and structure of football clubs were very much regimented, too – with little or no freedom to manoeuvre – which was in tune with the junta government. Players were expected to obey orders and were closely supervised; whether it was being told when they could eat or drink, or to having to be holed up in training camps days before matches.

Initially, Sócrates along with his team-mates went along with this structure. However, he felt suffocated – famously a man of peace and freedom – and with the dictatorship strangling the life out of democracy in Brazil, believed that it was a time for change.

Naturally, it was not something that Sócrates or his team-mates could openly discuss. Instead it had to be done subversively, behind the scenes and through the power of words. Many high-profile athletes in Brazil at the time were politically aware and felt that it was their duty to try to use sport to re-democratise Brazil and end the regime.

An agreement was reached with the new club president Waldemar Pires in the early-1980s which allowed Sócrates and his team-mates to have full control of the team and to establish a democratic running of the club. During a meeting in which everyone got an opportunity to speak freely, it was agreed that every decision would be decided by the collective. This would be when the squad would train, eat or, as Waldemar expressed in a documentary about the Corinthians team, “when they would stop on the coach for a toilet break”.

What made the Corinthians democracy even more unique was that voting wasn’t restricted to the playing and coaching staff; it was a model that involved everyone within the club. Whether it was the players, masseurs, coaches or cleaners, everybody had a say. In short it was ‘one person, one vote’ with everyone backing the majority verdict.

After agreeing the new structure it was first put to the test when Corinthians went on tour in Japan. Walter Gasagrande, who was 19 at the time, was heavily in love and wanted to fly back home to his girlfriend. A vote was called for with people speaking for and against Gasagrande being able to return to Brazil. It was decided that he would have to stay – and Gasagrande respected the decision.

Nothing was off-limits at discussions with it being agreed that a psychiatrist was to be hired in order to help the team. Sócrates and his colleagues had an open mind and invited people who interested them outside of football. Prominent artists, singers, and filmmakers were invited to speak on various topics.

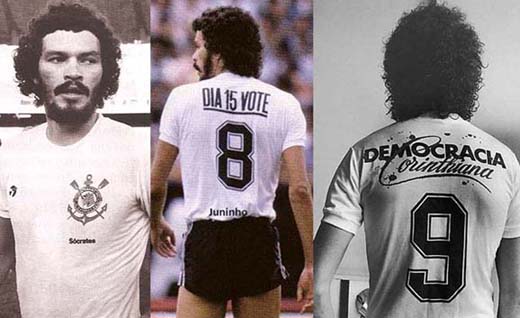

Corinthians slowly embodied the dream of the ordinary Brazilian in removing the dictatorship, to be replaced with universal suffrage. This was markedly expressed on the back of the club shirt which had ‘Corinthians Democracy’ printed with splashes of mock red blood similar to the Coca-Cola logo.

It was a move that upset the prominent right-wing, many of whom had branded the Corinthians’ Democracy movement as “anarchists” and “bearded communists”. However, with football coming to represent the very essence of Brazil even the junta government knew that they had to tread carefully. Nonetheless, the government still warned them about interfering in politics.

Indeed, they had used the success of the 1970 World Cup for their own devices, so much so that Sócrates stated: “Our players of the 1960s and 1970s were romantic with the ball at their feet, but away from the field absolutely silent. Imagine if at the time of the political coup in Brazil a single player like Pele had spoken out against all the excesses.”

Sócrates and his team-mates were prepared to bring in a silent revolution by using football to speak out against the military junta. The first multiparty elections since 1964 were set for the May provincial elections in 1982. Despite this, the majority of Brazilians were scared of voting. Some didn’t even know whether the army would allow them to vote, while others thought it safer not to vote at all.

With the May provincial elections set for the 15, the Corinthians team decided to up the ante and to chip away at the dictatorship. They agreed that they would have ‘on the 15th, vote’ on the back of their shirts to encourage people to head to the polls.

It was a quiet voice of dissent but as a smiling Sócrates advises in an interview years later, the military junta could hardly object as the team was not backing any particular party, merely encouraging people to vote.

Corinthians’ mood was quickly picked up by Brazilians, with the military government taking a battering in the provincial elections. It now appeared that the regime was losing its grip on power. Sócrates later said: “[It was the] greatest team I ever played in because it was more than sport. My political victories are more important than my victories as a professional player. A match finishes in 90 minutes, but life goes on.”

With the thirst for democracy at its peak, Corinthians now pushed for presidential elections. The team now took to the field with ‘win or lose, always with democracy’ emblazoned on their jersey this time. It was a mood that was quickly engulfing the ordinary Brazilian, who sensed that they could push for democracy.

During this period the Timão won the 1982 and 1983 São Paulo Championship. Unsurprisingly, considering his talent, Sócrates was highly sought after by top European clubs. In 1984, he proclaimed at a large rally that if congress passed through the amendment for free presidential elections then he would stay in Brazil. A huge cheer went up but sadly the amendment fell and Sócrates moved to Fiorentina.

Brazilians, in the words of Sócrates, were beginning to realise that political change was possible. It was something that the military government couldn’t stop, and so it was in 1985 that they were defeated in the presidential elections. Finally, Corinthians had achieved their objective of returning democracy back to Brazil.

It was a dream that Sócrates and the club were proud of bringing to the fore. By using football, they had managed to get their message across and helped bring about the change that people wanted. In many ways, it is quite fitting that since football is in the bloodline of Brazil, it was the Sócrates and the Corinthians Democracy that was part of the movement that helped rid the nation of the military government.

A first class player and man, there are few footballers with the same skill and integrity of the great Doctor Sócrates. It is why, after passing away in 2011, that he was revered with a fitting tribute by Corinthians players and supporters who held their fist out in memory of their legendary brother.

Socrates and the Corinthian democracy